FOR 23 years, without second thought, Bliss Broyard checked off boxes that would best describe her to herself as well as to the world: Upper middle class. Connecticut born. Prep school educated. White.

She was part of a handsome, well-respected WASP family: sister to a towheaded blue-eyed brother, Todd; the daughter of a dancer mother, Sandy, with "Nordic good looks"; and her father was the famously prickly, politically conservative book critic for the New York Times, Anatole Broyard, of French extraction, the family thought.

But that changed at 24.

Not all of it. Just one check mark in one box, a single modification. But for Bliss Broyard it altered everything. That year she learned a secret whose revelation would become legend in literary circles, then gradually radiate outward, finally inspiring her to write a just-published memoir, "One Drop: My Father's Hidden Life -- A Story of Race and Family Secrets." In 1990, just weeks before his death from cancer, Broyard's mother (after long prodding her husband to do so himself) gathered her children to tell them that their father -- despite what boxes he checked, despite how he had presented himself to the world -- was of "mixed blood," of Louisiana Creole descent, "part black" -- passing for white.

The idea that she and her brother were, by extension, "part black too" was exciting, Broyard recalls thinking. It made her feel like she "mattered in a way I hadn't before." But there was something unseemly hovering behind the necessity of the secret -- the scope, depth and weight of it. Ultimately her father slipped out of the world stamped and registered as a "white" man, and without discussing the details of his passing with his children. For Bliss Broyard, it was a curious question to consider: Late in the 20th century, what did it mean for her father to have "crossed over" and to have remained there? To have hidden it from his own children, to have cut himself off from extended family scattered throughout the country, as far as Los Angeles -- and in essence from himself?

In "One Drop," Broyard, now 41, grapples frankly with the pact her father made with himself. She doesn't seek to "unmask" him but to expose the circumstances that led to such a drastic choice, one with indelibly painful reverberations.

It took more than a decade for Broyard to try to make her way to the root of the impulse, to the why of the lie, and to sort out what it meant to inherit such a legacy of deception: "Overnight my father's secret turned my normal young adult existential musing of Who am I into a concrete question, What am I?" Broyard writes early on in "One Drop." "My mother had said that his secret caused him more pain than the cancer in his bones. I didn't want any shame clouding up my life. When people asked me what I was, I would tell them. But the question was, What exactly would I say?"

To understand why a man would have stepped out of not only his family but also his ancestry is to confront the United States' history of slavery, Jim Crow discrimination and the deeply rooted caste system built around the color of one's skin and the assumptions constructed around it. The "one drop" of the title refers to a regulation dating back to slavery that classified any American with the smallest trace of "black blood" as black and relegated anyone of mixed race/mixed parentage to the lower-status race.

"It's hard to visit this kind of history," Broyard says, "to meet family that your father rejected. A lot of it is incredibly painful." And yet, Broyard says, "these are the agents that shaped my father's life and mind."

There were a flood of questions to grapple with, the question of shame to address. And "I really did want to know beyond writing a book, 'What did I think about what my father had done,' " she says. "He was still larger than life when he died. I really loved my father and I really identified with him. So I wanted to make sense of it." Her father had built a fence around his new family and new life; had carefully pruned and tended his new identity. He'd attempted to erase all of the footsteps it took to get to that place. Had for the most part cut himself off from the rest of the Broyard clan. "Throughout my father's writing ran the theme that a person's identity was an act of will and style," Broyard notes.

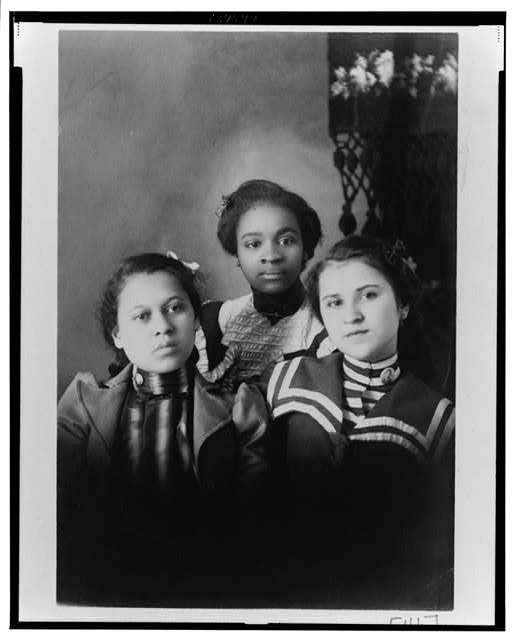

He was the lightest-skinned child of three children, and because both of his sisters, Lorraine and Shirley, lived as black, Anatole seldom, if at all, saw them in later years. Nor did he often see his mother, Edna. (His father died in 1950.) However, the long-hidden family made its appearance -- in classic passing-narrative fashion -- at Anatole's funeral, among the galaxy of literary friends and Connecticut bluebloods. After his death, the plot got thicker, more confusing with each new revelation, each casual anecdote from a family friend or former colleague:

It wasn't that he was openly denying anything, Broyard began to understand, but rather that he was actively eluding labels. And in retrospect, she realized, her father's racial identity was an open secret, something that had always circled in the back-space. "It's always difficult to point to one reason that something happened," says Broyard, who now lives in Brooklyn with her husband and daughter. "But my father had a great amount of unarticulated anxiety, rage and anguish about race."

Six years after his death, she was still struggling with the enormity of it. What finally jump-started her was Henry Louis Gates' 1996 New Yorker profile, "White Like Me," which became the first formal accounting of her father's "crossing over." Broyard was at first furious. "I felt that he had taken away my story." But in retrospect, she realizes that he saved her. Gates, she says, "took the responsibility off me . . . of outing my own father. He forced me to try to get into more conversation about it and to start shaping my ideas. And through him, it gave me the courage to go out and meet my family."

Then in 2001 came Philip Roth's novel "The Human Stain," whose main character was widely thought to be based on Anatole Broyard. It made Bliss Broyard even more eager to finish her own book.

Even the language of passing is full of polite evasion, and careful metaphor -- "crossing over," passed over" "went for white" -- and speaks to the attempt of concretizing something that defies easy explanation. For many African Americans, Anatole Broyard's racial sleight-of-hand is not an unusual or exotic story. "It won't be news," as Bliss Broyard concedes. But the complicated history of Louisiana might be to many people.

"Understanding particularly the Creoles from New Orleans was crucial in my understanding my father's racial identity," says Broyard. "Growing up in Connecticut, all I knew was the most common African American narrative -- you know, Middle Passage, slavery, sharecropping, Great Migration -- and my dad didn't fit into that." She needed to grasp that history with its myriad racial designations -- mulatto, quadroon, octoroon -- and a burgeoning class of free people of color, and an insulated Creole culture with its own language and customs.

Just what was her father wriggling out of? Sloughing off the "stain" of race? Being labeled a "black writer"? Escaping the prison that the "one-drop" rule put him in? Why not not be black if he didn't have to be? "I think his construction was, 'If not for prejudice, I wouldn't have to be in this conundrum.' So rather than holding the whites accountable for the prejudice, he held the blacks accountable. I guess," says the daughter in a small, aggrieved voice, "it's your classic self-hatred."

The more she came to know about Anatole Broyard, the less she began to know about the man she called her father. And while history and context helped explain why some family members chose to occupy an awkward space between -- to work as "white" but live as "colored" -- what would make her father decide to cut the ties completely? And who were those scattered people who lived on the other side of the line, who didn't see color as confining or as a blemish -- those he left behind?

In his Culver City home, Mark Broyard, whose father, Emile, was Anatole Broyard's second cousin, keeps the Creole traditions: He makes red beans and rice on Mondays, laundry day, and he still peppers the occasional sentence with patois. The artist and singer has turned his house into a veritable shrine to New Orleans, full of fleur-de-lis-adorned knickknacks, photos of generations of his family and his own artwork -- complex assemblage pieces that pay tribute to the city. But for all of his reverence to tradition, his love of New Orleans and the old, Creole ways, Mark Broyard has never identified himself as anything other than black.

His family moved to Los Angeles in 1960 when he was 3, but he'd always heard the talk: "I grew up knowing that there was this relation, a writer, Anatole Broyard, who was the book critic at the New York Times, but he'd passed over -- passe blanc -- that was the expression that they used all the time. So we never had any contact with him or his family," says Mark Broyard. "But if you look at the guy, he looks like other Broyards I know -- my dad, my Aunt Elaine. . . ."

Like Mark too.

He later learned the particulars in the New Yorker. And soon after, his cousin Bliss came calling. "There she was in these white-girl tennis shoes, you know -- skate shoes," he says. "I thought, 'Now, no black woman wears Vans! That's gotta be her.' But we hit it off immediately" and have been in touch weekly ever since.

"I just felt sad for Bliss. To be cut off from her heritage. From her family. Look at what she missed. -- the family stories, the culture. . . . So why? It just freaks my mind." Mostly because he doesn't understand why it was so "bad" to be black. "I give my mom and dad credit for staying in the 'hood." And his mother was always there to remind them: " 'Soft-peddle that Creole stuff because a lot of people don't want to hear it.' "

On this side of the divide, possessing ambiguous features was a daily Rorschach: "I've had all kinds of stuff happen to me on [all] sides. Growing up, I had my bike taken, my hair cut off with a steak knife for 'being a white boy.' White folks being nasty and rude to you. Black folks being nasty and rude," he says. "People come up to me and speak Spanish, and when you don't speak it back to them they think you're trying to pass. When I tell them that I'm black, they'll say: 'You're black? Why would you want to be black?' " He can only let out a rueful laugh. It's not a matter of choice for him. "It is what I am."

It was all of this, he says, "that Anatole wanted to avoid." But to what end?

"Everyone knew. So really, he was hiding from himself," explains Mark Broyard. "He wanted to make these literary strides. But the weird thing about it is that he never really made them. He couldn't write the great American novel because there was something all locked up inside of him. And if he told his story -- his real story -- it would have been great. Because he was living an interesting story -- 'How I infiltrated the New York Times,' " Mark says, rifling around for something, a moral to the story. "So maybe while he was embarrassing people, letting people down, maybe he did something profound."

Along with the many questions Bliss Broyard still has for her father, she also wonders: Would he have been happier if he'd stayed in the black community? Would he have been able to achieve his dream of being a writer of import, without constraints? But the larger question looms: Why couldn't he have lived in a moment when those didn't feel like two opposing notions?

Broyard thinks of herself now as someone of mixed-race ancestry -- checking several boxes -- white, black, Native American. "I don't think I can just claim African American identity because I wasn't raised that way, and yet I do feel that there's been a shift in my world view." That in-between space, acknowledging everything -- unlike for her father -- feels like a safe place to rest. "But I do hope, I really hope, that all this can further a conversation about what is black, and how blackness has been defined, the need and difficulty of being forced into these categories . . . I hope that the focus can be on that rather than what my father did."

lynell.george@latimes.com